The Surprising History of Flint Glass Works

26 November 2025

We explored the history of our Flint Glass Works venue and its rich historical prevalence in the industrial revolution. Starting as a glass mill in the 1800's, we went back and looked into what life was like at the mill and how we got here today.

Tucked away on the edge of Ancoats’ Urban Village, Colony Flint Glass Works is a quiet yet flourishing flexible workspace.

Long before it became part of the Colony network, the building began life as a 19th century glassworks factory.

Today, it spans four floors of private offices, meeting rooms and coworking areas, and if you look closely, its exposed brick walls, large windows and other character features all serve as a reminder of its industrial past.

In late 2024, the second floor of the workspace underwent a major transformation. Now, as we celebrate its completion, we’re taking a look back at where it all began…

From the original Flint Glass Works and Ancoats’ pivotal role in the Industrial Revolution to the area’s regeneration and the rise of a new modern workforce, this is the surprising story behind Colony Flint Glass Works.

Colony Flint Glass Works 2nd Floor, Ancoats, Manchester, 2025

(Image: Colony)

Flint Glass Works, Ancoats, Manchester, 1900s

(Image: Northern Group)

The Former Glassworks

Flint Glass Works first opened its doors around 200 years ago. Established in 1844 as Percival & Yates Flint Glass Works, it was one of several significant glassworks operating in 19th century Manchester.

In the early 1850s, Thomas Vickers joined the company, which became Percival, Yates & Vickers. Around a decade later, following William Yates’ departure, it was renamed Percival Vickers.

The factory was purpose-built with two glass furnaces, an annealing house and workshops. By 1863, it employed 373 workers, becoming the city’s largest glassworks. By 1880, a third furnace had been added.

During the 19th century, Manchester was England’s second major center for pressed glass production, surpassed only by the North East. By the 1870s, the city had around 25 glassworks, renowned for producing high-quality pressed glass.

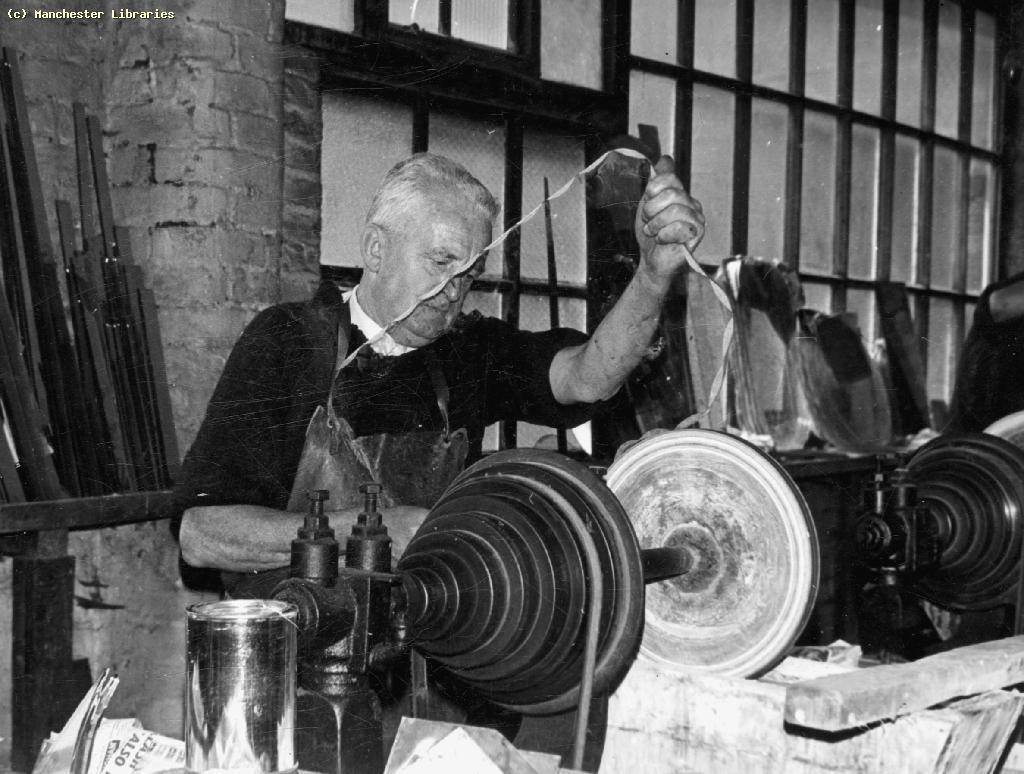

The city’s glass industry attracted skilled artisans from Europe, including Bohemian glass cutters such as William Florian Pohl, who engraved items like the Manchester Town Hall Goblet in 1877.

Percival, Yates & Vickers specialised in tableware made from (you guessed it) flint glass, where they pressed the softened glass into intricate moulded designs. Flint glass is produced by adding finely ground flint to molten glass and is still used widely today in cameras and microscopes.

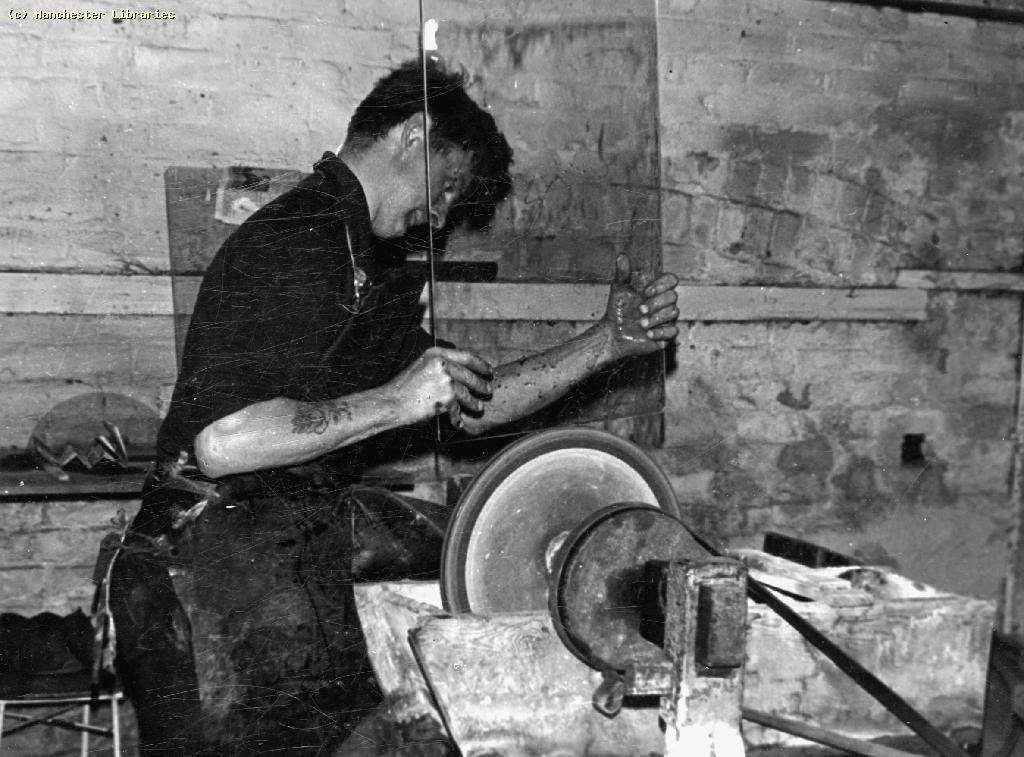

While rapid industrialisation brought prosperity to Ancoats’ factory and mill owners, life for the workers was far from glamorous.

In 1862, William Yates testified in a government commission report on child labor. Of the 373 workers, 48 were boys under 13, the youngest just ten years old. The youngest typically washed tumblers before taking on specialised roles as they grew older, becoming flatters, cutters, or glasshouse workers. The factory also employed 31 women, nine under 18, who mostly worked in frosting or stockroom roles.

Standard working hours were from 6am to 6pm, with variations in the glasshouses and during busy periods. Meal breaks were often shorter for glassblowers, who took them at their workstations, and night work was necessary for furnace operations.

Glass factory in Ancoats, Manchester, 1967

(Images: Facebook)

Historical Ancoats and the Rise of the Industrial Revolution

Picture Ancoats 200 years ago: red-brick mills, smog covered factories and cobbled streets forming the heart of Manchester’s Industrial Revolution.

Manchester did not gain city status until 1853. Before that, it was a market town surrounded by villages like Ancoats, where skilled textile workers converted attics and cellars into workshops.

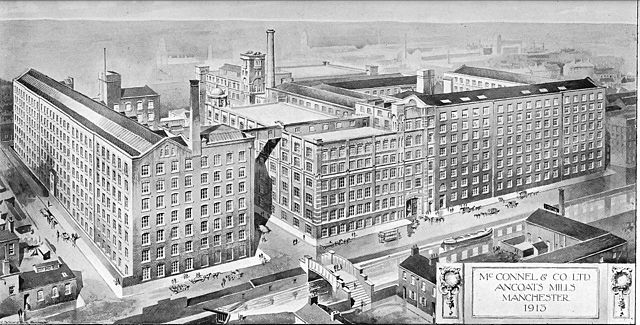

By the early 19th century, Ancoats was home to some of the earliest steam-powered mills and factories that transformed the textiles industry, earning it the nickname "Workshop of the world".

Ancoats Bridge Mill opened in 1791, followed by dozens of others. By 1816, there were 86 steam-powered mills in the district, including Murrays’ Mills, the largest. More mill complexes followed, such as Sedgewick Mill in 1818 and Beehive Mill in 1824.

By the mid-19th century, Manchester earned the nickname “Cottonopolis”, responsible for 32% of the world’s cotton textile production by 1871. Rapid urbanisation followed, with Manchester’s population growing from 84,000 in 1801 to 391,000 by 1851.

Ancoats became one of Britain’s most densely populated areas and the overcrowding led to poor living conditions - in 1841, the average life expectancy in Ancoats was just 26 years!

In German philosopher Friedrich Engels’ 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England, he described Ancoats as “Hell upon Earth.”

In 1851 Ancoats' total population was 53,737. Many immigrants from Ireland and Italy came to Ancoats in search of work at the factories and mills and tight-knit communities formed, bonded by shared labor and living spaces, including Irish and Italian immigrant enclaves like “Little Ireland” and “Little Italy.”

Fun Fact: Ancoats is credited with giving the world the ice cream cone. In 1901, Italian biscuit maker Antonio Valvona patented a method to serve ice cream in edible waffle cups, replacing the unsanitary “penny lick” glasses.

Ancoats Mills, Manchester, 1913

(Image: Wikiwand)

The Early 20th Century and the Decline of Industrial Ancoats

Flint Glass Works began to struggle before the First World War, and by 1914, the premises had been sold. Much of the original site was demolished over the 20th century. Textile production peaked in 1913, then declined due to competition from India and artificial fibers. By mid-century, many historic buildings in Ancoats stood abandoned. Populations dispersed to new estates like Wythenshawe, and large-scale slum clearance in the 1960s further depopulated Ancoats.

Jersey Street, Ancoats, Manchester, 1910

(Image: Facebook)

The Regeneration of Ancoats

Ancoats was designated a conservation area in 1989 to protect its remaining historic buildings. Throughout the 1990s, speculators began purchasing land for redevelopment, and by the late 1990s and early 2000s, Manchester City Council was leading the first phase of a long-term regeneration project. Many of the district’s former mills were transformed into residential and commercial spaces, and Cutting Room Square was created as a public plaza featuring concrete monoliths that showcase historic mill imagery.

Northern Group, Colony’s sister company, was among the first to recognise Ancoats’ potential and invest in its renewal. Just off Cutting Room Square, Colony opened its first venue - Jactin House - in 2017, later expanding into Flint Glass Works in 2023.

In October 2003, before redevelopment of Flint Glass Works, Oxford Archaeology North excavated the site, uncovering original glass furnaces and offering new insights into historic production techniques.

Today, Ancoats is a thriving neighbourhood filled with vibrant bars, restaurants, shops, and creative spaces. Fast-forward to 2025, and Time Out has listed Ancoats among the coolest neighbourhoods in the UK.

Edinburgh Castle, Cutting Room Square, Ancoats, Manchester, 2005

(Image: Facebook)

A New Way of Working at Flint Glass Works

Today, Ancoats has embraced a new kind of workforce, a far cry from the glassblowers and factory hands of 200 years ago.

Colony operates seven flexible workspaces across Manchester, including four in Ancoats. Flint Glass Works is home to a vibrant mix of tech start-ups, creative agencies, freelancers, and remote workers, all thriving in spaces once filled with furnaces and glass presses.

When Colony took over the building in 2023, we wanted to create something new and inspiring for the Flint Glass Works community. Working with design agency ‘kin, we commissioned Bristol artist, VOYDER, to produce a mural that would capture the spirit of the space. Drawing inspiration from the building’s history as a glassworks, he developed a unique steamed-glass effect through which the portrait is viewed. Located on the ground floor in the Floating Desks area, the towering image is as striking as it is serene, evoking both the familiar and the unknown.

For a long time the buildings basement floor, ground floor and first floor has housed private offices, meeting and conference rooms, as well as an open plan social kitchen and co-lounge. Now, following the completion of the second floor upgrades, the enhanced space also offers 17 new private offices, eight phone booths, four collaboration booths, a social kitchen, meeting room for up to 10 people, and a mezzanine floor with two screenshare booths and a chill out space with comfy seating.

If you’re looking for a private office in the heart of Ancoats with plenty of character and a rich history, email info@colonyco.work to book a tour today!

Colony Flint Glass Works Floating Desk Area, Ancoats, Manchester, 2024

(Image: Colony)